For years, American policymakers have been searching for a better framework to conceptualize the US-China relationship. After the procedural paradigm of engagement was judged to have failed, many lurched towards the “Thucydides trap,” which conceptualizes tensions as the inherent consequence of shifts in the balance of power. Others have attempted to look beyond this fatalism, aspiring to “managed competition” in which coexistence is possible. Some have attempted to introduce nuance — reframing tensions not as with China’s people or nation, who have legitimate aspirations for prosperity and security, but with the governing Communist Party — with mixed results.

The US has been right to recognize the competitive nature of its relationship with China. But it needs better language to conceptualize its contours and the tools of that competition. Just as there is no monolithic China, there is no singular competition. The relationship is subjected to all sorts of pressures with differing time horizons and degrees of acuteness that require different stabilizing mechanisms. And binary incentive and disincentive or hard and soft power frameworks betray the need for nuance. Better policy must first start with better frameworks for conceiving it.

A multi-faceted competition …

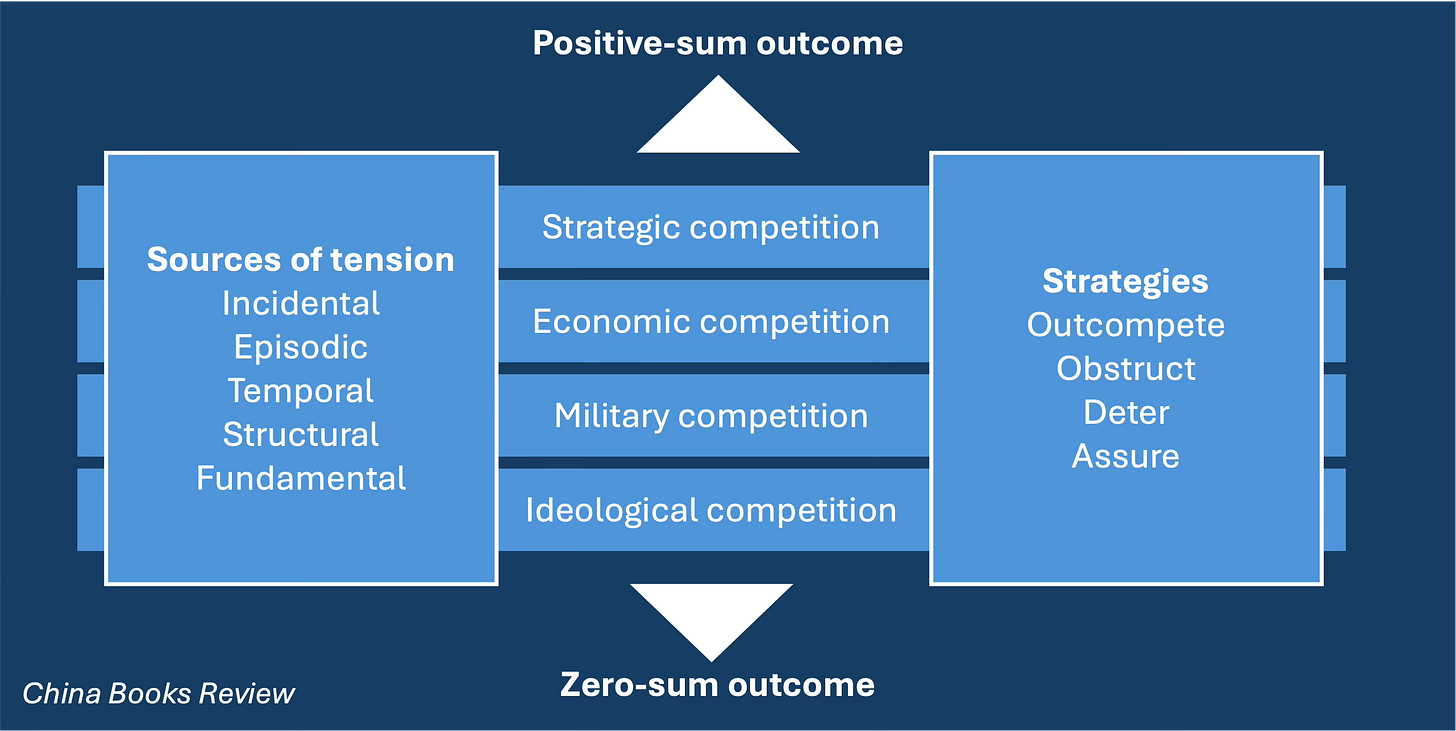

All countries, even close allies, compete. The question is over what, how, and whether that competition is positive- or zero-sum. The US-China relationship is characterized by four forms of competition:

a strategic competition for leadership over the global order;

an economic competition over who creates more value and whether it comes from tangible sectors (e.g., manufacturing) or intangible (e.g., finance, intellectual property) ones;

a security competition, currently centered on East Asia but with the potential to go global; and

an ideological competition over political systems and cultural influence.

Each competition is currently trending in an unproductive direction: exclusionary global blocs; a costly trade war; security dynamics that assume conflict is inevitable; and an ideological rivalry marked by mutual swings between arrogance and self-doubt. But an alternative is possible: one in which the United States and China act as responsible stakeholders in a reformed global system; use their economies to advance innovation and global development rather than coercion; achieve strategic stability; and respect pluralism.

… with varied sources of tension …

Five types of tension cut across these domains of competition:

Incidental tensions that stem from unexpected events, like a military accident. These usually allow for de-escalation;

Episodic tensions that arise from recurring moments, like Taiwan’s elections, and temporarily raise risk;

Temporal tensions caused by the confluence of specific sociopolitical factors, such as the challenging combination of Xi Jinping and Donald Trump as leaders of their respective countries;

Structural tensions, which include mistrust inherent to different political systems (and the perverse bureaucratic and political incentives that can favor tension within each system); the status of Taiwan; and the destabilizing effects of China’s export-led growth model; and

Fundamental tensions, which are shaped by the extent to which either side believes that the other constitutes a permanent and existential threat that must be contained or defeated, risking a self-fulfilling spiral.

Different tensions require different types of engagement. Incidental tensions call for hotlines and ongoing military exchanges. Episodic tensions benefit from mutual access to trusted backchannels; temporal tensions require long-term investments in exchanges that can produce leaders with more sophisticated mutual understanding; structural tensions demand dialogue mechanisms and broad working-level relationships between governments; and fundamental tensions need sustained norms of regular leader-level exchange. Both countries have been uneven in developing these mechanisms and are guilty of disregarding parts of them in the moments in which they are most needed.

… and a need for nuanced approaches

American foreign policy has often been framed in Hamiltonian, Jeffersonian, Jacksonian, and Wilsonian archetypes. In the Trump administration, those archetypes have been cast aside in favor of new camps: “prioritizers,” who seek to husband America’s power for the China challenge; “primacists,” who focus on capability expansion; “crusaders,” who link order to moral purpose; and “culture warriors,” who see global liberalism as an extension of domestic progressivism.

These camps differ on two axes: how positive-sum they believe the future can be, and how much they favor cooperation over autonomy. Regardless of their disposition, they rely on the same toolkit. Here, the framework of “hard” and “soft” power often fails policymakers because it often invites blurring of the instruments of power and domains of competition. For example, the ability to deploy economic sanctions may flow from a country’s relative position in the economic competition, but can and does target any domain of competition.

Instead, it is better to think about strategic intent: to outcompete, obstruct, assure, or deter a rival. All approaches are needed in some combination for each domain of competition:

America’s naturally competitive economic system is being challenged by a determined practitioner of industrial policy: it is relearning how to better focus and support its economic actors without compromising their performance.

As it does so, the US continues to overindex on strategies of obstruction, including technology controls, in ways that may be increasingly self-defeating.

The US military has long assured the country a formidable degree of deterrence, but as this is challenged by China, it is struggling to reorganize and rearm itself for a new paradigm of conflict.

The US has generally underleveraged assurance, which is needed to rebut perceptions that it seeks to thwart China’s rise.

Know thyself

Many US-China tensions originate as much from internal challenges as from the pressures they exert on each other. America’s include abdicating strategic competition in favor of a transactional foreign policy; excessively focusing on military competition over other domains; investing more in decrying unfair economic competition than in its own competitiveness; and losing confidence in and a willingness to defend the soundness of its system. All of these challenges, while difficult, remain within its capacity to solve.

China, by contrast, refuses to acknowledge competition. Instead, it continues to speak of “win-win cooperation” while declaring Taiwan, democracy and human rights, its political system and trajectory, and its right to development as four “red lines [that] must not be challenged.” The Communist Party has also conflated itself with the nation, positioning itself as the arbiter of Chinese civilization. This has distorted a structural issue — the difference in the two countries’ systems — into the perception that the United States is fundamentally unwilling to accept China’s rise. As a result, the Party’s imperatives for self-preservation come at the nation’s overall expense: Taiwan is reduced to a test of legitimacy, other countries' political systems become fields for interference, and the economy is oriented to serve the end of power, not prosperity.

Instead, each of these “red lines” can be reframed as factors or outcomes of competition. If so, Taiwan’s future would no longer be solely a matter of military competition, but return to a test of whether China can offer an appealing alternative to the Taiwanese people — or whether China’s system can evolve beyond using Taiwan as a measure of its legitimacy. In a competition framing, China would see less need to engage in political interference abroad and meet the United States’ demands for greater reciprocity with confidence. It would stop thwarting its own development by embracing economic reform and convert a current source of structural tension into a stabilizing force. In embracing competition, China would recognize that its system’s strength has always been in its flexibility and adaptiveness, not its rigidness.

Winning the long game

The United States cannot impose change on China, but it can influence China’s perceptions of it. This begins with a commitment to self-renewal that can arrest the prevailing assumption that the US has begun an irreversible decline. The US can also exercise the forbearance needed for China to ultimately change itself, avoiding measures that lock future Chinese leaders into confrontation. Consistent, multidimensional engagement is essential. Diplomacy should be conducted with the steadfast knowledge that other forms of engagement — commercial, educational, and cultural — have created pathways for China’s people to change their own lives, if not yet their system.

This is a moment that calls not just for new limitations on engagement, but experimentation and, indeed, selective boldness. The US should act on the reality that nuclear arms control has a better chance of reaching accommodation than most other issues. The US should also welcome the billions of Chinese investment in less sensitive sectors that would be implied by job creation offers floated early in the Trump administration. It is not enough to call for 50,000 American students to visit China, as Xi Jinping did in his 2023 visit to San Francisco: every child in America should have a Chinese pen pal, anchoring empathy in the next generation. Ordinary Americans and Chinese have more in common today than most in either country recognize, despite fleeting moments on social media. Those whose lives bridge both societies know another way is possible.

If the US can reconceptualize its understanding of the competition, it will be better placed to articulate what it wants from it, better manage the drivers of — and impediments to — that trajectory, and deploy the strategies needed to reinforce or arrest these trends. America’s marketplace of ideas, on China as much as anything else, still offers the promise of getting to a better outcome.